Athens Social Meltdown

Freelance filmmaker Ross Domoney, recounts his experiences over the past two years covering protest and social unrest in Athens.

Originally published in Open Democracy.

1st May 2010

I first encountered Athens by accident. It was 2010 and I was supposed to be covering a demonstration in Lithuania. Days before my flight, I met a Greek girl at a skate park in London. Despite not being able to speak Greek beyond “yamas” (cheers!) and her limited English, we maintained online contact. At the very last minute, our conversations spurred me to decide to fly to Athens, with the ambition of covering the May Day protests.

Kindly hosted by the girl– I was humbled by the hospitality I received in Greece, even from strangers – I experienced smoky bars filled with incessant heated and political debate. Whilst I sought to take part, I knew my comments were most certainly naïve; at the time, I knew but a few things about Athens, from the occasional riotous image I saw in the news and terms like “austerity” which were jargon to me at the time.

What caught my attention, however, was the exhilarating atmosphere of the city. During the first Greek demonstration I attended on the 1st of May 2010, the mass of people at the city centre were defiant in the face of the militarized police force that stood in front of them. In this thrilling atmosphere, the crashes and booms of stun grenades echoing off buildings excited the film maker in me immensely.

As May Day came to an end I was running through a neighbourhood called Exarcheia. Little did I know that this would become home for many months down the line. The neighbourhood runs behind the Polytechnic University in Athens. As we passed the university, a Greek friend advised me to hide my camera. Whilst putting away my gear, we noticed a group of masked men sitting by the gates of the University, fiddling with Molotov cocktails. For the rest of the afternoon, a series of cat and mouse games of violent clashes played out between the two sides, somehow avoiding any injury.

Both knackered and energized by the day, I figured that May Day would be my one and only experience of a demonstration of that kind during my stay in Greece. Little did I know that this would be just the start of my relationship with Greece; as I enjoyed Ouzo with friends, I was told that the general strike on the 5th of May would be another experience worth capturing.

5th May 2010

Faster than I would have wanted it to come, 5th of May arrived and as I walked out of Syntagma Metro Station, I was startled by hundreds of thousands of people pushing towards the Greek parliament, as if at the cusp of storming parliament. As I managed to climb the stairs, I found my way to the front. The view below me made me gasp, there was not a single clear patch of ground to be seen. As I analyzed what I had before me, I noticed the concerned faces were not only of hardened anarchists or communists, but of protestors representing a cross-section in society.

The police themselves were shell-shocked, confounded by the sheer amount of people at the demonstration that day.

A general strike was called that day, to publicly express outcry over the first bail-out package from the International Monetary Fund. After many stones, molotovs and canisters of tear gas - the police finally managed to battle the thousands of people down from the stairs of the Greek parliamentary building.

As I returned back to Syntagma Square, the sounds and sights of the clashes caused a sense of fear in me, this was a spectacle I had never experienced. It looked like the whole of Athens city centre was embroiled in protest, unrecognizable for most. As I saw smoke rising from a street parallel to Syntagma and decided to head over, a person running past told me that a bomb had gone off at a bank.

In front of the bank, an angry crowd was being pushed back by police whilst a camerman was being beaten by the crowd, his camera ruined by paint thrown at it. I kept my camera and gear on the low to be cautious.

The word soon spread that someone had firebombed the bank, the only bank to stay open on the day of the General Strike. Tragically three bank workers were trapped inside, as the manager had supposedly locked the back door. All three perished in the fire, including a woman who was pregnant.

The mood on the streets instantly changed. Many were shocked and saddened by the deaths and people slowly retreated to their homes. Images of the the bank soon found their way to mainstream media outlets who blamed anarchists and public demonstrations for the attacks. The talk on the streets was that it could well of been a provocation, done deliberately by the state to distract and take people off the streets. Whether true or not it sure did work, the streets were empty.

As I returned truly exhausted by the days commotion, I was met by a friend in tears: my jacket still reeked of teargas. She had prepared a welcome BBQ for me that evening with a group of friends, and as we sat around the table listening to the radio relay the tragedy that had happened inside the bank, the mood plummeted. There was a real feeling of uncertainty combined with a fear of what the bail out package would result in if passed by parliament the following day.

6th May 2010

Next evening – finding myself outside parliament again with a crowd that did not match the mass of the previous day but was still considerable – everyone was listening into the radio to hear the result of the austerity vote. Not before long, the police were ordered to disperse the crowd and baton charged everyone that stood in their way.

This particular demonstration would stay in my mind for a long time to come, an old lady next to me had been hit on the head with a truncheon, blood was pouring down her head. I soon learned how broad the struggle had become, with even the elderly targeted by the police.

Soon enough, a volley of stun grenades sent us all running. Later in 2011, videos of elderly women throwing rocks at the police would appear on the internet.

The incident with the elderly lady contested the idea that the protests were confined to a small section of angered youths. The lady was clearly no physical threat, she was merely caught in the middle when the police decided to beat back the crowd. It was remarkable that no further deaths resulted that day or in the successive rock throwing, motorbike attacks, and police shield-beatings that occurred in protests thereafter.

It was as if strikes had taken on a form of ritual; in the following anti-austerity protests, lines were drawn by protestors and the police, if either would cross the lines, things would get messy. In one incident a man was sent flying to the floor by a police motorbike patrol after the bike was deliberately driven into the man, inducing a huge roar from the crowds. A demonstrator took out a Molotov cocktail and lunged it towards the police but this time aimed directly at the perpetrator of the bike attacks head, igniting his face. Dramatic images of what appeared to be a low intensity civil war were captured that day and spread around the world as testament of what anti-austerity protests could lead to.

Returning home

I left Athens in May 2010 in a state of numbness, which I understand often happens when you experience something huge but are still in the process of digesting it. I had witnessed the historical opening chapter of what was to be known internationally as "the Greek crisis", and it was the closest to a rebellion I had ever seen. I had never really seen burning barricades, petrol bombs and a police force which almost lost control as it did in front of parliament. Thinking back to Athens in those days, there was a real sense that the people could defeat the decisions of the unpopular parliament.

I spent days scanning all my negatives from Athens; many of the pictures I couldn’t even remember taking. I would then be reminded of the stories behind the pictures, but I still was not aware of just how significant May 5th would be in changing Greek society and securing the implementation of austerity for the coming years.

From my laptop in England, I would come to learn of what the deaths of the three perished bank workers would mean for the movement in Greece. We would not see petrol bombs fly in Athens until December that same year. A collective feeling of guilt and reflection hit the more radicalised anti-authoritarian elements of society. If young kids were responsible for the action, then should it be up to the older activists to provide guidance on "revolutionary" protest tactics? Many believed that it was bound to happen, the Marfin Bank was one of the only banks open on the day of the general strike, the back doors shouldn´t have been locked. Much reflection was done, and the Government were quick to use the opportunity to crush the atmosphere which led to the spectacular social explosion that took the streets of Athens on May 5th.

For the rest of that year I remained in the UK, I documented street violence spurred by a movement that stood ideologically opposing to the movement in Greece, that of the English far right. Although I touched on the worrying development fueled by the right in the UK, I had no idea that I would experience a much more serious far right movement in Greece.

15th December 2010

I returned to Athens in December 2010 in order to visit a friend, this time I packed my video camera “just in case”. Whilst I read an Athenian newspaper in English on my flight I was brought to the attention of another General Strike announced for the 15th of December, thankfully I had packed my gas mask as a "just-in-case" precaution.

As I prepared for the strike, I figured I would dress all in black, with my leather jacket and black jeans, to disguise myself inside the lines of the Athen’s anarchist bloc. The idea was not to just video behind the lines of the police, as most would. I did not know what to expect from the demonstration, as Greece hadn’t featured in the news since the events of May 5th.

As I entered central Athens from Omonia Square, the sea of people may not have been as large as they were in May but there were still a considerable amount. The crowds appeared tired but still determined to demonstrate. Despite an air of anxiety among the different blocs marching towards Syntagma square, one could sense a great anger boiling under the surface.

This time round at Syntagma, the police line was a considerable distance from the steps of Parliament. I was filming the police tightening the straps of their gas masks as a bloc of demonstrators on the frontline did the same. The bloc linked arms with a combination of hands and sticks. Paint bombs were thrown from the crowd and splattered the cops, and almost simultaneously large booms echoed off the walls of the nearby Hotel Britannia. This and other hotels surrounding Syntagma have balconies that fit around the square like a diadem, it is worth noting that many of these hotels would offer spaces to journalists for large sums to film the view of the protests from above. It is unfortunate that when the international media had focused on Greece, most of the images came from these balconies, and not from the streets below.

Going back to that first boom, it bizarrely served as some kind of whistle blow which spurred the start of a violent game all too common in the big demonstrations in Athens. It suddenly seemed like large blocs of anarchists and young fighters where fighting the police on every corner of Syntagma. At the same time, people from all walks of life where shouting at the building of parliament or the police. Some elderly citizens even had gas masks, whilst others just took the tear gas defiantly with a mere handkerchief covering their mouths. A number of molotovs, gas bombs, tear gas canisters and stun grenades where thrown around the centre in what was becoming an increasingly violent riot. A 4x4 was a blaze outside the front of the Hotel Britannia. Apparently, although without confirmation, some people leave their cars deliberately on the main streets on days of strikes, so that they can claim on insurance a new one if their car becomes burnt to a shell.

By then, a feeling of rage was in the air and I saw the police take a beating on several occasions. A large crowd ran up a street, which turned out to be the same street that Marfin bank was on before it was burnt out a few months earlier. I was running up through a cloud of tear gas, hopping over stun grenades amongst a bloc of anarchists who were fighting police lines as they came across them. I filmed as they chipped the concrete away from ledges to throw at the police and although I was wearing black, I was not always confident of people's reaction if they saw me filming. I composed my shots without any immediate hostility. Soon we were to reach burning bins outside the Polytechnic university.

As some of the last militant blocs of demonstrators march past Skaramanga squat, a roar of solidarity screamed it's way out of the building's windows. The blocs soon met a large gang of around 30 motorbike police and the two groups clashed, stick to stick, helmet to helmet. The police were weakened and one point, I even saw students hitting the police with their own batons which they dropped in the battle, and a police officer running to hit someone with an anarchist flag that he found dropped on the road. It was all rather contradictory, while men threw rocks at the police, women would walk past minding their own business, while men in balaclavas fought the police, there were undercover police dressed the same making arrests.

Returning home again

When I returned to the UK after yet another wild experience in Athens, I sought to it to read into the modern history of the Polytechnic University and its surrounding neighbourhood, Exarcheia. I learned of the 1973 revolt which was organised in this university against the military Junta, with students having called a gathering there through radio in order to demonstrate discontent against the dictatorship they had been living in. That movement ended when army tanks literally crushed the gates of the university, killing many students. Every year on the 17th of November, a commemoration event happens at the site; itself often ending in riots.

I read into an equally symbolic event that occurred on the 6th of December of 2008. In a neighbourhood that was renowned for being a bastion of anarchist grass routes politics, a place where the police knew of antagonism. A second large revolt occurred there, after a police man shot and murdered a 15 year old boy called Alexandros Grigoropoulos in cold blood. The shooting sent shock waves through Exarchia, the killing enraged Greek society as if one of their own family had been killed. Even grandmothers in the neighbourhood were said to have thrown plant pots down from their balconies at the police.

At the time, the Greek state did little to reconcile with these fractions and when the biggest Christmas tree in Europe was propped up in Syntagma Square that same December, it was symbolically burnt down. Even though the state would deny its importance, some believed these occurrences served to highlight the cracks that preempted the current Greek crisis.

For the first half of 2011, I was caught up finishing my degree in London and other projects tied to the course. I watched Athens from a distance, unable to see it from the ground. At the same time, Ben Ali in Tunisia had been ousted, Cairo was amidst a revolution and squares were being occupied in Spain and Greece. I was told that I was missing on important developments in Greece, of the hundreds of thousands people gathered in Syntagma under no union flag or political party, curating a new form of people’s democracy in their propped up tents. When yet another bitterly unpopular round of austerity measures were signed off by the Greek government, the Syntagma movement ended in another large street battle. As soon as my university course was over, I purchased a one-way ticket to Athens.

A band plays music as an anti-austerity demo marches past

17th November 2011

After reading about Exarcheia and coincidently ending up there in the two trips prior, I figured this would be the place to stay. After checking into the Hotel Exarchion amidst the ripe political graffiti that covers nearly every wall of the streets in Exarcheia, I stepped into a building that had the anarcho-syndicalist flag flying from its top balcony not knowing what to expect. I was a little uneasy walking up the steps I had no idea what it would be like inside, or if the people inside would be welcoming to outsiders. I wondered how I would explain what I am going to do whilst I was there, I was told there was hostility towards cameras, especially in a neighbourhood like this. The space inside turned out to be lovely: a cozy smokey bar in a beautiful building with wooden floors and large windows. As the song “Jeepers creepers” was playing on the speakers and I ordered a beer at the bar, I instantly felt more relaxed. I found out that the space was not a squat but a social centre called Nosotros, and I would make good friends there. As I chatted away with my newly made friends about the 17th of November commemoration demonstration that was coming up, I remember a very charismatic girl telling me that "if the cops come, drop your camera and use your head!" as she head butted the air with some force but a smile on her face.

Leaving the hotel after some days, I was updated with information of what to expect in the run up to the 17th of November. There were anarchist meetings at the Polytechnic university and the plan was for all the various anarchist blocs to march as one on the day of the demonstration. Inside the University, amongst a sea of black clothing there was a gallery showing black and white pictures of the students who lost their lives in the 1973 uprising. There also were videos that played out scenes of the huge riots which took place around the university on various 17th November anniversaries. A couple of black clad groups of men guarded the entrances of the university with sticks and helmets, a few bins were burning outside.

As you walked around the University, you would find Marxists, Trotskyists, Anarchists, Anarcho-Syndicalists, and Communists alike. Beautiful revolutionary Greek music was playing, many of the songs from the era of the Greek Civil War. People would visit throughout the day to place flowers on the battered gates that were twisted by the tanks that entered the university in 1973. I remember seeing an elderly man with his granddaughter who carefully placed a flower on the gates as he held her hand. His teary eyes stared into space like he was reflecting back on those old days with a nostalgia and a regret for the world that his granddaughter was growing up in.

On the 17th of November, as I drank a coffee in Exarcheia square, there were a few protestors gathering with flags. Police were well briefed for the day of action, a routine demonstration that occurred every year since 1973. 7,000 policemen arranged to guard the centre of Athens and as the roads filled with people, chants grew louder and echoed off surrounding buildings. As we reached the corner approaching Syntagma there was a real feeling of not knowing what was about to happen.

We got around the corner and met an incredibly heavy police presence as the blocs began to surround parliament. Some blocs had planned to storm the police lines simultaneously but by the time we got there, a bloc had already started attacking from the road that leads up to the left side of parliament. As molotovs were thrown at the police, tear gas would come back in retaliation. The concerted plan of action inevitably failed and what resulted was another chase game, we spent most of that day and night running away from the police. Back in Exarcheia, there was still some movement – mostly just small barricades and blocks to stop the police from entering the area. As we wrapped up the day with a dinner amongst friends, one of them confessed, “I feel depressed, I was expecting more of today”.

The next commemorative demonstration was on the 6th December, the anniversary of the death of the 15 year old, Alexis Grigoropoulos, who was shot by Greek police in 2008. Since the demonstrations of the 17th November, I had started to acknowledge that planned demonstrations in Greece were unlikely to be anything out of the ordinary. The police and state could expect what was to come from these commemorative demonstrations, and protests did not necessarily appeal to wider spheres of society.

I did notice, however, that foreign Europeans would come to these two protests in particular, either in solidarity or to report on the events.

6th December 2011

On the day of the 6th of December, I visited the spot where Alexis was shot. As people gathered around the memorial stone donned with flowers and candles, they stood silently, some where crying. As the memorial lies close to a cluster of cafés and bars, it was hard to envisage how such a cold hearted incident could have occured there, the action was sure to provoke a reaction.

I had a separate video report to cover that day on the tourist area of Monistiraki. As I was on the job, I remember walking up Ermou street to find hundreds of students covered in malox – the spray used to deter tear gas - stampede down the street. The light smell of tear gas was evidence that some clashes had already occurred at Syntagma square, it made me more eager to finish the job and go cover the demonstrations.

Soon enough, I arrived where thousands of people had gathered. As the march began a group of teenagers splinted from the group and began chipping concrete away from the ground with hammers, as others would pull out Molotov cocktails from their comrades’ rucksacks. As the march reached the periphery of the parliament, a line of rope separated the crowds from the line of police guarding the steps. Despite the line, the rope was soon stepped over. Shortly after, stones and molotovs began flying from the hands of protestors towards the police. It was mainly teenagers clashing with the police, as the older activists stood by to watch the very theatrical riot unfold, some were advising against certain actions. The stun grenades from the police were followed by a new kind of weapon: one that would bounce off the road, split into three and explode. The grenade had the capacity to deafen or blind if it bounced off the road in the wrong way, not to mention the damaging effect of the tear gas on your lungs. It worked to dispel the resistance, and soon most had retreated back to Exarcheia.

In Exarcheia, clashes continued to take place late into the night. The police would tease; coming into the central square, they would throw chemicals before retreating back to the side streets. Various pockets of resistance would attempt to keep the police out of the different corners of the square. You could see various side streets light up with orange, followed by a crowd of people running back from a barrage of stun grenades. A squad of 12 riot police hastily moved toward the square, street lamps would light their faces and guide their eyes to cover as much ground as possible. In return, you could hear the rocks ricocheting off lampposts, as they would fly out from the darkness and towards the police in the light.

I foolishly removed my gas mask at one point, and was caught off guard as a tear gas canister was thrown right in front of me. Blinded in panic, and finding it hard to breathe, as I leaned up against a wall to put my gas mask on I heard the rhythmic sound of police batons smashing against shields. The police had charged forward and were right in front of the demonstrators. I ran as fast as I could, still blinded and practically choking expecting myself to either run into a lamppost or get clobbered by the police.

The feeling of suffocation scared me, but a kind man at a kiosk offered me some water to pour on my face and cool down. As I began to fully see again, to my amazement, I saw a man holding a petrol bomb in one hand queue up to purchase a lighter. He politely asked for a lighter, paid for it, ignited the Molotov and threw it at the line of police that had just chased us.

After the 6th of December, I returned to the UK for Christmas. I was yet to publish the film documenting the anniversary as I was awaiting for a worthwhile interview that would make the film more than just ‘riot porn’. I used this time to reflect and take a step back; I still had no concrete idea as to what the theme and purpose of my footage (from my whole time spent in Athens) was going to be, but my archive of videos started to become quite large. I soon heard from friends and saw through videos posted on Facebook that there were hundreds of thousands of people gathered against another austerity package that was to be signed off by the Greek government. As I heard of news of 50 buildings torched in Athens, I was disappointed in myself for having missed such a momentous event.

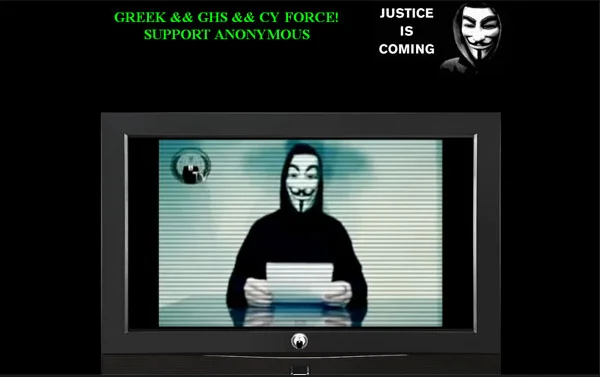

One morning, I woke up to find that one of my videos from Athens had reached 30,000 hits in one night and I was baffled. Looking at the analytics, it appeared that the video was syndicated onto the Greek Ministry of Justice’s homepage. Clicking on the link, Anonymous had hacked the site and it was my video of the 6th of December events that followed their video statement. Whilst I was fascinated to have it picked up by Anonymous at the same time I was concerned that I might be called in to questioning, and wondered if I was would encounter problems re-entering Greece.

I soon booked another flight back to Athens to pick up where I had left off and faced no problems at the Greek border. This time round, I had found the atmosphere of the streets very tense. The police clearly felt that they had lost control of the centre of Athens the weekend prior, judging by their presence on every street corner of the centre. For a week or more, I was routinely searched, most probably because I was young and could be 'hiding explosives in my rucksack'. This tedious process culminated with greater angst when in one occasion I got chased by the Delta motorbike (notoriously fascist) police on foot just after they had searched me 10 minutes prior. One policeman barged me into a wall and had me surrounded by him and his cronies. As he stood there with a stone cold glare, his commander recognised my face and that he had just searched me minutes before.

Yet another demonstration happened the day after I arrived, I captured on film a powerful moment wherein a woman was crying to the police. Whilst I had no idea of what she was saying, I could still feel her despair and emotions.

Tensions were running very high that evening again, I witnessed a middle-aged man being beaten by young men in masks. It was a brutal scene to witness, the man’s head was being kicked into the concrete on grounds of his connection to the Greek government, apparently enough of a justification for a severe beating. As five riot police officers wrestled a teenager involved in the attack to the floor, he fought one of them defiantly and as he attempted to rip his helmet off he tried to sink his fingers into the policeman’s eyes.

The police resorted to tear gas once again, pushing the group back towards Exarcheia. As two squads of riot police closed in on the crowd, I got stuck in the middle with nowhere to run. One policeman knocked me down and soon a gang of them surrounded me and began to beat me with their shields. Just as I thought I was done– people started to throw rocks and drew their attention away, giving me a chance to leg it and escape. I jumped in a taxi for the short distance home that night.

The human cost of the crisis:

As the weeks went by in Greece, I had secured myself a very reasonably priced flat to live in and began to better gauge the general mood in Athens; it was pretty grim. The year prior had been full of street resistance, but this year that energy had somewhat dissipated. The effects of the austerity measures were becoming a day to day reality with the police still acting with impunity against members of the public. Whilst the effects of the budget cuts were somewhat hidden, you had to look no further than the streets to see the human cost of the crisis. Homelessness burgeoned across central Athens and the sight of people searching for food through bins became commonplace; the saddest image for me was to see the elderly have to suffer. I saw an old man on my road looking through garbage one evening and felt like I had to help him, as I smiled and tried to start a conversation, but as he saw me from the corner of his eye he felt so embarrassed to have been seen that he ran away immediately. Violence was no longer confined to demonstrations either, as we commonly understand the violence of Athens. Walking past a homeless person and not being able to do much to help that person is violence. You can’t help every person that comes to you and asks for a donation, but it seems that walking past him or her without recognizing his or her existence is now commonplace in Athens.

23rd March 2012

On March 23rd, I experienced another surreal event on this day that is historically celebrated in memory of the Greek defeat against the Ottoman occupation in 1821. Judging by the current state of affairs, however, many considered this day of national parades a joke; how could the government celebrate a national triumph in Greece’s current situation. The police even took oranges down from the trees in Syntagma, in case they were thrown at the politicians. Athens was in complete lock down with police everywhere and snipers on various rooftops of central buildings. The crowds were completely controlled, and only those with special passes, were allowed into the crowd, to clap as school children marched past.

This was the one and only time I was treated politely by a riot cop in Athens. He saw me filming the school children marching past the politicians and gently guided me to a near by wall to get a better shot. Around the corner, things were far from normal. Some teachers were holding a protest against the austerity measures that had radically cut their wages and were being beaten back violently by the police. Again, I saw elderly people subjected to violence and, this time, people arrested for filming.

4th April 2012

On the morning of 4th April I got a text from a friend and it read, “an old man has killed himself with a pistol in Syntagma square”. As I arrived, a band of musicians were playing for the tourists who were walking past, everything looked totally normal. I managed to finally find a lonely candle by a tree, commemorating the 77 year old Dimitris Christoulas, next to it lay a pool of thick fresh blood. The lonesome flame was slowly populated by more and more candles as people began to gather around. Some laying down flowers and saying prayers, others just staring. Some would clap at the tree with a combined look of fear, desperation and anger: the collective sorrow of Greek society at the moment. As the day went on and thousands gathered, a young girl read out his suicide letter on a megaphone. The letter read, “for soon I will have to be searching for my own food in the garbage”. Other parts were clearly political and called for the youth to take up arms.

That evening, the police tear gassed the square. A journalist had his skull cracked by the police and another woman was sent to hospital. I remember seeing teenage girls being beaten around by the police, which particularly infuriated me.

Days later at Dimitris Christoulas’ funeral, powerful scenes unfolded as thousands attended. His coffin was bought through the crowd as friends and relatives read out heartfelt speeches. Slowly after, the funeral turned into a protest that headed again to Syntagma. The atmosphere was understandably highly charged; as a police car drove past on the opposite road, it was pelted with objects thrown by the crowd.

Grandmothers chanted loudly as they walked past parliament and I suddenly heard shouting in the square: a crowd had surrounded someone on the floor. I ran over to see a man laying face down in a clotty pool of blood. He was being severely beaten in ways that will be hard to forget. Eventually, the crowd stopped spitting and beating him and the wrecked man was led away. It turns out he was a police officer who had apparently sworn at the crowd who had left the funeral of Dimitris Christoulas. He had been stripped off his uniform (including his gun) and beaten to a pulp. His police outfit was burnt and it’s remains hung from the tree Dimitris Christoulas shot himself under.

Whilst this was happening, we would also hear the stories of Golden Dawn, especially as the elections approached. Then a neo-fascist movement and now a party with seats in parliament, whose acts of violence were becoming a nightly occurrence in Greece. You would hear of migrants being beaten and even killed. There was a strange feeling in the air when this group, previously unknown (internationally), grew into a large scale social movement. There were large anti-fascist demonstrations in response, and public outcry toward the actions of a neo-Nazi organisation soon to gain political power.

May 2012

In May, on the night of the first round of elections, everyone was talking. Would the radical left, anti-austerity party of Syriza take the votes and bring Greece out of its crippling program of austerity? Foreign journalists flocked to Athens for the elections, expecting unrest – but what came was rather unexpected. The movement was, in a sense, quiet around the turbulent political months of the elections, people were waiting to see how the next political chapter of Greek politics would unfold.

That night I watched the elections at a social center in Exarcheia. Eyes where glued to a smokey projection shown onto the wall. As we watched, we saw that Golden Dawn, had gone from holding 0.3% of votes in 2009 to a shocking 7.0%. Some said they had foreseen their potential in securing a larger proportion of the electorate as a result of the fear and desperation that Greek society was subject to. There was even talk of Golden Dawn entering Exarcheia that night. We all imagined scenarios in our heads; people prepared themselves for an attack just in case.

In a way, without liking the sound of it, a fascist uprising was gradually unfolding in Greece. Attacks on migrants increased to eventually occur nearly every night, in Athens particularly. With statistics from local poll stations suggesting that nearly 60% of police officers serving in Athens on the day of the elections voted for Golden Dawn, it is hard to deny the police’s tacit role in attacks on migrants. From what I had seen, they were often provocative and racist toward migrant groups of the city.

Scenes would later unfold that resembled a low intensity war in the neighborhood. Anti fascist motorbike patrols where formed , migrants would applaud as the bloc of bikes, which would at times carry several hundred people, patrolled the streets. One time a clash with fascists lead to the arrest of 15 people from the Antifa patrol. The police as on many occasions, protected the fascists. Whilst inside the police headquarters of Athens some of the 15 arrested were tortured, including women. The police officers, which were members of the Delta motorbike unit, took pictures of the arrested and threatened to send them to Golden Dawn.

By the end of May, I was feeling the need to leave Athens and return to England for the summer. I missed people close to me, while the task of deciphering what was happening socially on the streets of Athens required some distance. I needed time to collect my thoughts outside the dark mood that surrounded me. I therefore planned for my return to the UK for after the second round of elections in June.

In the run-up to these second elections, Golden Dawn fared equally well despite one of their MP’s slapping and verbally attacking a female member of the Communist Party on TV without retribution. With the lead taken by the right-wing conservative party New Democracy, society was again bound to a path of greater austerity measures. New Democracy was to head the current coalition government, themselves showing signs of racism, claiming in public speeches that the city had been taken over by invaders (migrants). There was media attention on the militant left, but the right appeared to get away with contestable actions and provocations unscathed.

After the last round of greek elections, I was more than ready to come home. I felt trapped in a grid of social uncertainty that I for one found it hard to make sense of. Where as I felt I had succeeded in capturing the street politics of Athens, my work still felt un-complete. In a way, as much as the experience added depth to my understanding of the Greek crisis, it simultaneously posed many more questions I am yet to decipher. I do know that the crisis goes far beyond Greece's border, the scenes I experienced in Athens are recurring in capital cities across the world. What striked me about Athens however, was the remarkable defiance of Athenians to stand up to social meltdown. My only hope is for the same in other countries, before it's too late and such defiance becomes a necessity.